The Acid Spectrum in Hot Sauce: pH, Safety, and Flavor Choice

Quick Scope

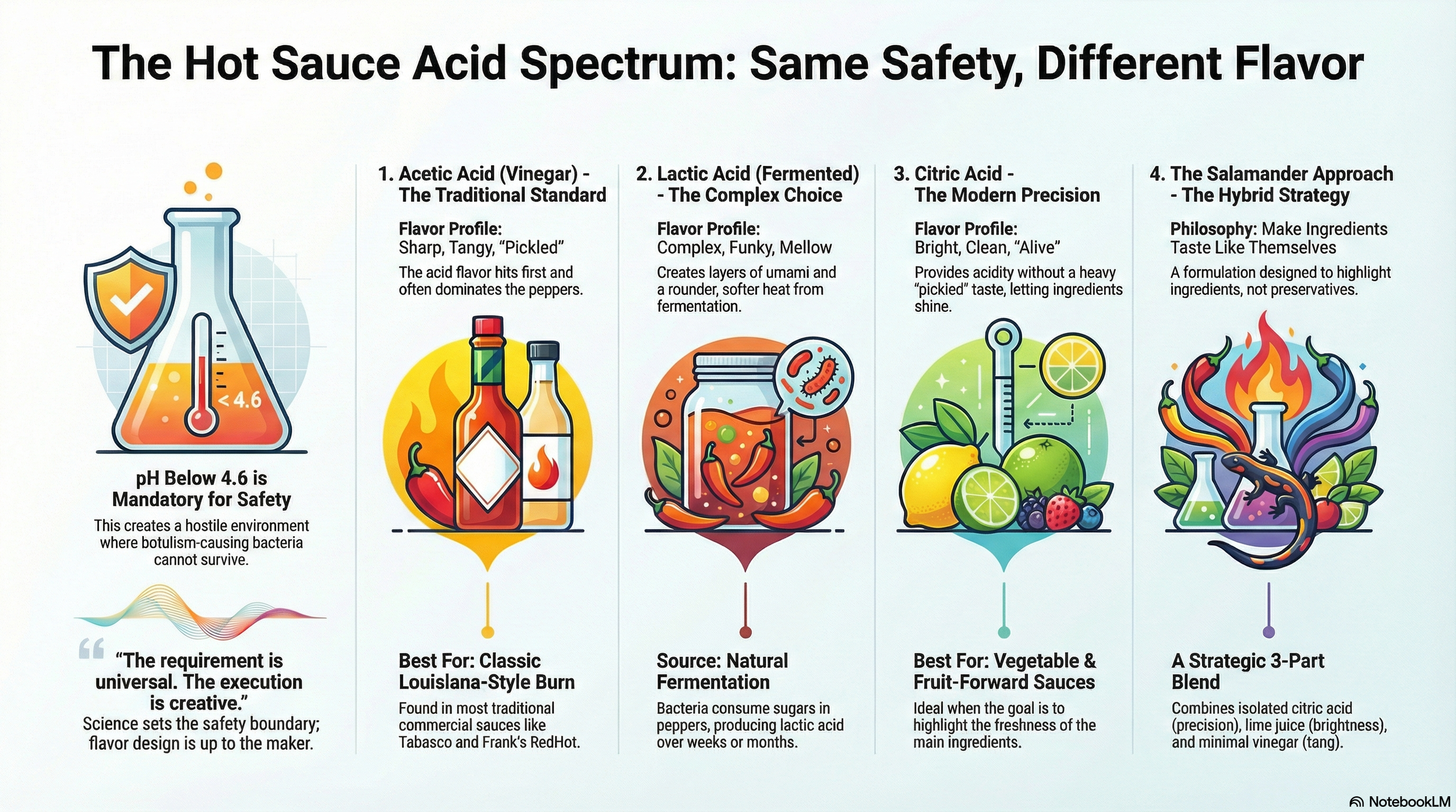

The five primary acid types in commercial hot sauce—acetic, citric, lactic, malic, and fresh citrus—and how each achieves pH <4.6 safety while creating completely different flavor profiles. From vinegar's pickled tang to citric acid's clean brightness to lactic acid's fermented funk: same safety threshold, entirely different sauces.

Salamander uses three acids instead of one — that's the difference: citric acid for clean brightness, fresh lime juice for authentic citrus, and minimal vinegar for familiar tang. pH 3.7-3.9 safety while vegetables taste like vegetables, not preservation.

Pick up two hot sauces with identical pH levels—both 3.8, both perfectly safe—and taste them side by side. One screams vinegar. The other brightens with citrus. One tastes pickled. The other tastes alive. Same safety threshold. Completely different flavor. This is the acid spectrum: where science meets choice.

By Timothy Kavarnos, Founder | Salamander Sauce Company

In our previous exploration, we saw how vinegar became the dominant preservative not by choice, but by necessity—proven to survive 19th-century supply chains long before anyone understood the science. Vinegar won through empirical proof: generations of people not dying. Economics later reinforced this dominance, but survival came first.

This post explores what happens when modern science lets you control for safety while choosing your acid not by shelf life, but by flavor. When scientists connected pH below 4.6 to botulism prevention in the 1920s, that understanding unlocked something profound: the mechanism was acidity itself, not vinegar specifically. Suddenly, the door opened to achieve that same safety using different acids—citric, lactic, malic, or combinations. Each creates wildly different flavor profiles while hitting the exact same safety threshold.

The question isn't whether citric acid or lactic acid or combinations are as safe as vinegar. The FDA settled that decades ago. The question is why an industry that knows this still builds 90% of its products around a single acid type chosen in 1895. That tells you more about infrastructure than chemistry.

The Structured Takeaway

The Fact:

pH below 4.6 prevents botulism in shelf-stable hot sauce — an FDA mandate for acidified foods. Above 4.6, Clostridium botulinum produces deadly toxin in sealed bottles. Below 4.6, it cannot survive. The mechanism is hydrogen ion concentration, not any specific acid molecule.

The Data:

Five acid types achieve the same safety threshold with different flavor results. Acetic acid (vinegar): sharp, pickled, dominant — used in 90%+ of commercial sauces. Citric acid: bright, clean, vegetable-forward. Lactic acid (fermentation): complex, funky, mellowed. Malic acid: fruity, tart. Fresh citrus: authentic but batch-variable. Salamander's three-acid system (citric + lime + minimal vinegar) hits pH 3.7-3.9.

The Insight:

Acid choice is a creative decision about flavor, not a safety constraint. Bacteria can't distinguish between acid molecules — only pH matters for microbial prevention. Vinegar dominated through historical momentum and economics, not because it creates superior flavor. Modern formulation unlocks what ancient fresh sauces delivered: pepper and vegetable flavor without preservation taste dominating every bite.

The Acid Spectrum at a Glance

- Acetic Acid (Vinegar): Sharp, pickled, reliable. The traditional choice. Dominates most commercial sauces.

- Citric Acid: Bright, clean, precise. Can be isolated or from citrus. Allows vegetable flavors to shine.

- Lactic Acid: Complex, funky, mellowed. Created through fermentation. Adds depth and umami.

- Malic Acid: Fruity, tart, sharp. From apples and stone fruits. Less common in hot sauce.

- Fresh Citrus: Natural citric acid with variability. Lime, lemon, grapefruit. Authentic but inconsistent batch-to-batch.

The Hot Sauce Acid Spectrum: Four approaches to achieving the same safety requirement (pH below 4.6) with completely different flavor outcomes.

In This Post

Science didn't just explain tradition. It unlocked alternatives. Understanding the mechanism lets you choose your method.

The Non-Negotiable: pH Below 4.6

Every shelf-stable hot sauce must maintain pH below 4.6. This isn't marketing. This isn't preference. This is microbiology.

Clostridium botulinum—the bacteria that produces botulism toxin—cannot grow when pH drops below 4.6. Above that threshold, even slightly, and you've created an environment where the bacteria can thrive in sealed, anaerobic bottles. Below it, and you've created a hostile environment where botulism can't survive.

The FDA mandates this threshold for acidified foods. It's not a suggestion. Every commercial hot sauce producer tests pH obsessively. Batch testing. Process validation. Documented records. The safety requirement is absolute.

But Here's What Changes Everything

Same pH. Different Acid. Completely Different Flavor.

pH measures hydrogen ion concentration. That's it. It doesn't care WHERE those hydrogen ions come from. Acetic acid at pH 3.8 and citric acid at pH 3.8 are equally safe from a botulism prevention standpoint. The microbes can't tell the difference.

But your tongue absolutely can.

This is where hot sauce formulation becomes creative. The requirement is universal. The execution is up to you.

Acetic Acid (Vinegar): The Traditional Standard

What It Is

Acetic acid (CH₃COOH) is the primary component of vinegar. Commercial white vinegar is typically 5-8% acetic acid diluted in water. Apple cider vinegar, wine vinegar, and malt vinegar all contain acetic acid as their active preservative compound, though they add different flavor notes from their fermentation sources.

When you see "distilled vinegar," "white vinegar," or simply "vinegar" on a hot sauce label, that's acetic acid. Some labels list "acetic acid" directly—this is the same compound, just named differently for labeling purposes.

How It Tastes

Sharp. Tangy. Pickled. Acetic acid creates the flavor profile most people associate with "classic" hot sauce. It's the Louisiana-style burn—that immediate tang that hits the front of your palate before the heat arrives.

The tang is aggressive. It doesn't hide. When vinegar is the first or second ingredient, it dominates the flavor profile. Peppers become supporting players. The sauce tastes acidic first, spicy second.

This isn't bad—it's just a specific choice. If you grew up on Tabasco or Crystal or Frank's RedHot, that pickled burn is what "hot sauce" means to you. It's nostalgic. Familiar. Reliable.

Why It Dominated

Acetic acid won through empirical proof decades before anyone understood the science. Vinegar didn't dominate because it tasted best—it dominated because bottles survived stagecoaches, warehouses, and temperature fluctuations. By the time scientists connected pH to botulism prevention in the 1920s, vinegar had already been the standard for over a century. But the mechanism they discovered—pH below 4.6, not vinegar specifically—means the reason vinegar won isn't the reason it still dominates.

Economics reinforced this dominance. Vinegar is cheap at scale. It's consistent batch to batch. It's familiar to consumers. Once the infrastructure was built around vinegar formulation, there was little incentive to explore alternatives. The system wasn't designed for flavor—it was designed for survival. And nobody rebuilt it.

When to Use It

Acetic acid works brilliantly when you want that classic pickled flavor or when formulating sauces meant to mimic traditional Louisiana-style profiles. It's also extremely effective in small amounts as a secondary acid—adding just enough tang to brighten a sauce without dominating it.

Citric Acid: Bright, Clean, Precise

What It Is

Citric acid (C₆H₈O₇) occurs naturally in citrus fruits—lemons, limes, oranges, grapefruit. It's what makes citrus taste tart and acidic. In commercial food production, citric acid can be isolated from citrus or produced through fermentation of sugars using Aspergillus niger (a common, safe mold used in food processing).

Isolated citric acid is a white crystalline powder. It's pH-neutral in its dry form but creates acidity when dissolved in water. Here's the critical point: food-grade citric acid is chemically identical whether it comes from a lime or from fermentation. The molecule is C₆H₈O₇ regardless of source. Your body can't tell the difference. Neither can the bacteria. The compound is the same—only the production method varies.

How It Tastes

Bright. Clean. Vegetable-forward. Citric acid provides acidity without the heavy, pickled character of vinegar. The tartness is there, but it's subtle. It doesn't announce itself. It supports the other ingredients instead of overwhelming them.

Peppers taste like peppers. Vegetables taste like vegetables. The acid creates the safety threshold while staying in the background. You get brightness without dominance. In a sense, this is a modern return to the flavor profiles of ancient fresh consumption—where Aztec chilmolli tasted of ground peppers and herbs, not preservation.

Fresh lime juice delivers citric acid naturally, but it brings variability—limes harvested in different seasons have different acidity levels. Isolated citric acid allows precise pH control batch after batch while maintaining that clean citrus character.

If you've spent years thinking you don't like hot sauce, there's a good chance you actually just don't like vinegar. That sharp, nose-wrinkling smell when you open a bottle of Tabasco or Frank's? That acrid bite that hits before you even taste the peppers? That's acetic acid doing exactly what it's designed to do: preserve through aggressive sourness.

For decades, the equation was simple: hot sauce = vinegar + peppers. If you didn't like vinegar, you were out of luck. The market assumed everyone either loved that pickled burn or tolerated it for the heat.

Citric acid changes that equation completely. Open a bottle of citric-based sauce and you smell peppers first—habaneros, bell peppers, whatever vegetables are actually in there. The acid is present (it has to be for safety), but it doesn't announce itself. It brightens rather than pickles. The difference isn't subtle.

What Changes Between Acids

With Acetic Acid (Vinegar):

- The smell hits you first—sharp, pickled, unmistakable vinegar

- The taste arrives as tang before heat

- The finish is sour, acidic, lingering

- Your impression: this is preserved food

With Citric Acid:

- The smell is peppers and vegetables—what's actually in the bottle

- The taste is heat and flavor arriving together

- The finish is clean, not sour

- Your impression: this is food that happens to be preserved

Both sauces hit pH 3.7-3.9. Both prevent botulism. Both sit safely on shelves for months. The safety is identical. The experience is not.

People who've avoided hot sauce for years because they "don't like hot sauce" often discover the issue wasn't the category—it was the acid. The moment they try a citric-based formulation, the response is immediate: "Wait, this doesn't taste like pickles. This actually tastes like peppers."

Why Salamander Uses It

When you build a sauce around habaneros, bell peppers, carrots, and tropical fruits, you want those flavors front and center. Citric acid lets them shine. We combine isolated citric acid for precision with fresh lime juice for authentic citrus brightness and minimal distilled vinegar for familiar tang. The result hits pH 3.7-3.9 (well below the 4.6 threshold) while tasting alive—not pickled.

This isn't about being "different for different's sake." It's about delivering the flavor I want: heat that transforms food through complexity, not acid burn. That's been the principle from the start.

When to Use It

Citric acid works brilliantly in vegetable-forward sauces, fruit-based hot sauces, and any formulation where you want acid to support rather than dominate. It's ideal when your goal is to showcase ingredients, not mask them.

Lactic Acid: Complex, Fermented Funk

What It Is

Lactic acid (C₃H₆O₃) is created through fermentation. When beneficial bacteria (primarily Lactobacillus species) consume sugars in vegetables, they produce lactic acid as a metabolic byproduct. This is the acid behind yogurt, sauerkraut, kimchi, and traditional fermented hot sauces.

Fermentation-based hot sauces like Tabasco or craft fermented varieties rely heavily on lactic acid. The peppers are salted and left to ferment for weeks or months. As fermentation progresses, pH drops naturally as lactic acid accumulates.

How It Tastes

Complex. Funky. Mellowed. Lactic acid creates a rounder, softer tang than vinegar. It has depth—layers of flavor that develop during fermentation. You taste umami. You taste funk. The heat is mellowed, not sharp.

Fermented sauces don't taste "bright"—they taste aged. Developed. Traditional. The acidity is there for safety, but it's woven into complex flavor rather than screaming at you.

Many fermented sauces add vinegar after fermentation to boost acidity and ensure pH stays below 4.6 consistently. This hybrid approach—lactic acid from fermentation plus acetic acid from vinegar—combines the complexity of fermentation with the reliability of vinegar.

When to Use It

Lactic acid shines when you want depth, complexity, and the distinctive character that only time and microbes can create. Fermented hot sauces appeal to people who love kimchi, sauerkraut, and aged flavors. It's a legitimate approach to preservation and flavor development—just a different choice than fresh formulation.

Malic Acid and Other Options

Malic Acid: Fruity Tartness

Malic acid (C₄H₆O₅) occurs naturally in apples, cherries, and stone fruits. It creates sharp, fruity tartness—less pickled than vinegar, more assertive than citric acid. It's less common in hot sauce but appears in fruit-forward formulations where apple or stone fruit character complements peppers.

Fresh Citrus Juice: Natural but Variable

Fresh lime, lemon, or grapefruit juice provides citric acid naturally. The advantage is authentic citrus flavor—real juice, not isolated acid. The disadvantage is variability. Citrus acidity changes by season, growing region, and ripeness. Batch-to-batch pH consistency requires careful testing and adjustment.

Many craft producers (including Salamander) combine fresh citrus with isolated citric acid—using juice for flavor and isolated acid for precise pH control.

Flavor Design Tools: Choosing Your Acid Based on Intent

| Acid Type | Flavor Profile | Best Use Case | Common In |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic (Vinegar) | Sharp, pickled, tangy | Traditional Louisiana-style sauces | Tabasco, Frank's, Crystal, most commercial sauces |

| Citric | Bright, clean, subtle | Vegetable-forward, fresh formulations | Salamander, craft fresh sauces, fruit-based sauces |

| Lactic (Fermented) | Complex, funky, mellowed | Aged, traditional fermented sauces | Craft fermented, Korean gochujang-style |

| Malic | Fruity, tart, sharp | Fruit-forward specialty sauces | Apple-based sauces, stone fruit blends |

| Fresh Citrus | Authentic citrus, variable | Premium sauces prioritizing fresh ingredients | Small-batch craft, high-end specialty sauces |

Experience the Citric Acid Difference

Taste how bright, clean acidity lets fresh vegetables and tropical fruits shine—without heavy vinegar tang.

Try Salamander SauceThe requirement is universal. The execution is creative. Science set the boundary. We choose how to work within it.

Why Understanding the Acid Spectrum Matters

When you understand that pH below 4.6 is the requirement but acid choice is the creative decision, you can make informed choices based on flavor preference rather than assumptions about safety or tradition.

Reading Labels with Knowledge

The next time you read a hot sauce label, look at the acid sources. If you see "distilled vinegar" or "white vinegar" listed first or second, expect sharp, pickled tang. If you see "citric acid" or "lime juice" before vinegar, expect brighter, cleaner acidity. If the label mentions fermentation or aging, expect complex lactic acid character. The acid order tells you the formulation philosophy before you even taste the sauce—once you know what the ingredient list is actually revealing.

None of these choices makes a sauce "better" or "worse" from a safety standpoint. They're all achieving the same pH threshold through different paths. The question is which flavor profile you prefer—and now you have the knowledge to choose consciously rather than assuming "vinegar = traditional = better" or "fermented = ancient = superior."

Respecting All Approaches

Vinegar-based sauces earned their dominance through 150+ years of proven safety. Fermented sauces carry centuries of tradition and develop flavors only time can create. Citric acid formulations allow fresh vegetables to shine.

All three approaches are legitimate. All three hit the same safety threshold. Understanding the science doesn't mean rejecting tradition—it means choosing consciously based on the flavor you want.

The Salamander Philosophy

We use citric acid not because vinegar is "bad" or "cheap," but because it delivers the flavor profile we're after: fresh vegetables, tropical fruit complexity, heat that transforms through layers rather than acid burn.

The combination of isolated citric acid (for precision), fresh lime juice (for authentic brightness), and minimal distilled vinegar (for familiar tang) hits pH 3.7-3.9 while letting habaneros taste like habaneros and bell peppers taste like bell peppers.

That's the choice we made. Your preference might be different. Now you understand why the options exist.

For 100 years, we trusted vinegar because it worked. Now we understand why it worked—and that opens the door to choices the Aztecs would have recognized: heat that transforms through fresh vegetable complexity, not acid burn.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do all hot sauces need to be acidic?

Shelf-stable hot sauce must maintain pH below 4.6 to prevent Clostridium botulinum growth. This bacteria produces deadly botulism toxin in low-acid, sealed environments. Acid drops pH below the threshold where botulism can survive. This is an FDA requirement for acidified foods, not optional. Every commercial hot sauce tests and validates pH to ensure safety.

Is citric acid natural or synthetic?

Citric acid occurs naturally in citrus fruits. Commercial citric acid can be extracted from citrus or produced through fermentation of sugars using Aspergillus niger (a common, safe food processing mold). Both methods produce identical compounds—the molecule is the same whether it comes from a lime or from fermentation. Food-grade citric acid is considered natural by most standards.

Which acid is healthiest in hot sauce?

From a health standpoint, different acids are functionally similar when consumed in hot sauce quantities. All provide acidity. None carry significant calories. The health differences in hot sauce come from other ingredients—sodium content, presence of fresh vegetables, absence of additives like xanthan gum. Acid choice impacts flavor, not nutrition.

What's the difference between using vinegar and citric acid for hot sauce preservation?

Both achieve identical safety—pH below 4.6 prevents botulism regardless of acid type. The difference is entirely flavor. Vinegar (acetic acid) creates sharp, pickled tang that dominates the sauce profile. Citric acid creates bright, clean acidity that lets vegetable and pepper flavors come through. Neither is safer than the other. The choice is about what you want the sauce to taste like.

How does fermentation affect the acid profile of hot sauce?

Fermentation produces lactic acid through bacterial metabolism—Lactobacillus species consume sugars in peppers and produce lactic acid as a byproduct. This creates complex, mellowed, funky flavor that develops over weeks or months. Many fermented sauces still add vinegar afterward to ensure consistent pH below 4.6, creating a hybrid lactic-acetic acid profile with both fermented depth and reliable safety.

How do manufacturers test pH in hot sauce production?

Commercial producers use calibrated pH meters that measure hydrogen ion concentration precisely. Each batch is tested. Meters are calibrated with standard buffer solutions. Results are documented for FDA compliance. Some producers also send samples to third-party labs for validation. pH testing is obsessive in commercial food production because the consequences of error are severe.

Can you taste the difference between acids at the same pH?

Absolutely. Two sauces at pH 3.8—one using vinegar, one using citric acid—taste completely different. Vinegar creates sharp, pickled tang. Citric acid creates bright, clean acidity. Lactic acid from fermentation creates complex, mellowed funk. pH measures safety (hydrogen ion concentration), but flavor comes from the acid molecule type and surrounding compounds.

Why does Salamander use multiple acids instead of just one?

Salamander combines citric acid (for clean brightness and precise pH control), fresh lime juice (for authentic citrus flavor), and minimal distilled vinegar (for familiar tang). This combination hits the safety threshold (pH 3.7-3.9) while creating the specific flavor profile we want: vegetables and fruit forward, heat that transforms rather than burns. It's strategic formulation, not random mixing.

Is one acid type safer than others for hot sauce?

No. Safety comes from pH level, not acid type. Acetic acid at pH 3.8, citric acid at pH 3.8, and lactic acid at pH 3.8 are equally effective at preventing botulism. The bacteria can't tell the difference between acid types—only pH matters for microbial safety. Choose acid based on flavor, not safety assumptions.

Can I blend different acid types in homemade hot sauce?

Yes—blending acids is how many craft producers (including Salamander) achieve specific flavor profiles. You might use citric acid as the primary acidifier, add fresh lime juice for citrus character, and include a small amount of vinegar for familiar tang. The key is testing final pH to ensure it stays below 4.6 regardless of which acids you combine. A calibrated pH meter is essential for safety validation.

The Bottom Line

The acid spectrum isn't academic. It's the single biggest factor in how your hot sauce tastes—more than pepper variety, more than heat level, more than what's on the label. Every bottle on the shelf made a choice about which acid to use, and that choice shapes everything from the first smell to the last bite.

Now you know the options. You know that safety comes from pH, not acid type. You know that vinegar dominated through historical momentum, not flavor superiority. And you know that citric acid, lactic acid, and blended approaches all achieve the same safety threshold while delivering completely different experiences.

The science just tells you the options exist. The story tells you why only one option dominated for 130 years—and why nobody thought to question it. That story isn't about chemistry. It's about stagecoaches, industrial accidents, and equipment built for problems that don't exist anymore.

Understand the complete preservation story

From ancient fresh consumption to modern acid formulation—see how hot sauce evolved over 9,000 years.

Read the Full Series📚 Continue the Discovery

- → The Villain: How 1895 safety crises locked the industry into a single acid choice for 130 years

- → The Precedent: What hot sauce tasted like for 9,000 years before vinegar

- → The Mechanism: Why pH 4.6 became the line between safe and deadly

- → The Answer: What happens when you rebuild from flavor instead of accepting the 1895 standard

About Timothy Kavarnos

Timothy founded Salamander Sauce after years working New York restaurants—front of house and kitchen, describing dishes, pairing wines, tasting with chefs, learning what makes people light up. That experience shaped his approach: sauce that works with food, not against it. Brooklyn-based, still tasting every batch.

Sources

- FDA 21 CFR Part 114 — Acidified Foods regulations and pH 4.6 threshold

- University of Georgia National Center for Home Food Preservation — acid types and food safety

- Food Chemistry, Belitz et al. — chemical properties of organic acids in food

- Salamander Sauce Company production records — pH testing and acid formulation data

Salamander Sauce Company. Born in Brooklyn, made in New York's Hudson Valley. All natural, low sodium, clean label.